This week, Google quietly offered a glimpse into a future where artificial intelligence can generate entire 3D worlds on demand—and the results were equal parts fascinating and deeply flawed. Using an experimental tool called Project Genie, I was able to create rough, AI-generated knockoffs of iconic video game environments, including worlds that looked suspiciously similar to Super Mario 64, Metroid Prime, and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

The experiences were amusing, sometimes impressive, and often bizarre. They were also a reminder that while AI world-building is advancing quickly, it remains a long way from delivering anything close to a polished, playable game.

Project Genie is built on Genie 3, Google DeepMind’s latest “world model,” a type of generative AI designed to create interactive virtual environments based on text prompts or images. Google first revealed Genie 3 last year, but access was limited to a small research preview. Starting this week, Project Genie is rolling out more broadly to Google AI Ultra subscribers in the United States, marking the first time many users can directly experiment with the technology.

According to Google, the goal is exploration rather than immediate productization. “It’s really for us to learn about new use cases that we hadn’t thought about,” said Diego Rivas, a product manager at Google DeepMind. Potential applications range from visualizing scenes for filmmaking and building interactive educational tools to helping robots learn how to navigate real-world environments. Still, Google is careful to temper expectations. “This isn’t an end-to-end product we expect people to use every day,” said research director Shlomi Fruchter.

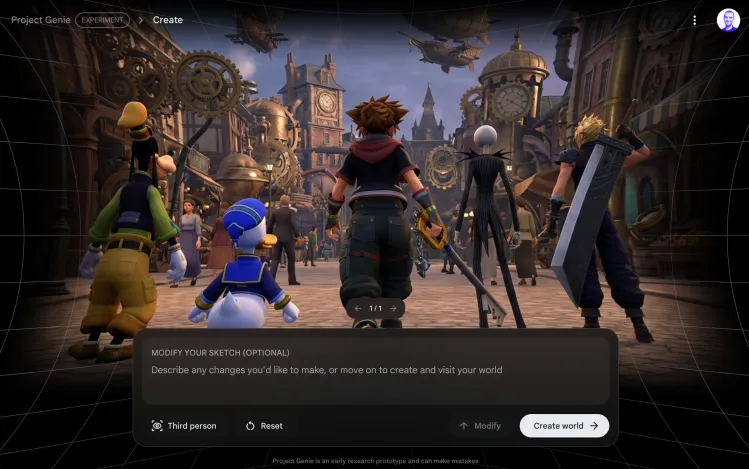

Using Project Genie is straightforward. Users can choose from a selection of pre-designed environments or write prompts describing the world and characters they want to create. After a short processing delay, Genie generates a thumbnail preview and then renders a fully explorable environment. Each world lasts just 60 seconds, runs at roughly 720p resolution, and targets about 24 frames per second. Navigation is simple: WASD keys to move, the space bar to jump, and arrow keys to control the camera.

The problem is that the experience often feels more like a technical demo than an actual interactive world.

One Google-designed environment, called Rollerball, places the player in control of a blue orb rolling across a stark, snowy landscape, leaving a trail of paint behind it. There are no objectives, no sound, and no clear sense of progression. Input lag is severe, making movement feel sluggish and unresponsive—worse than many cloud-gaming services. Over time, the world begins to feel unstable: paint trails disappear, mechanics stop working, and the environment fails to remain visually consistent.

Another environment, Backyard Racetrack, offers slightly more structure with a defined course to follow. While marginally more engaging, it suffers from similar issues. Portions of the track unexpectedly morph into grass mid-run, breaking immersion, and vehicle details appear poorly rendered. The lag makes precise control nearly impossible.

Where Project Genie becomes more entertaining—if not more useful—is when users push it to its limits. Prompting the system to generate worlds inspired by well-known gaming franchises produced crude but recognizable results. A Mario-like platforming environment, a Metroid-style sci-fi landscape, and a Zelda-inspired open world complete with a paraglider all emerged, though none offered meaningful gameplay. There were no goals, scores, enemies, or challenges—just space to wander and jump.

Even that limited interaction was frequently undermined by lag and inconsistency. At times, character controls stopped responding entirely, leaving only camera movement. The worlds often felt like they were being re-imagined frame by frame rather than remembered as a coherent space.

Notably, Project Genie showed inconsistent enforcement of intellectual property boundaries. While it allowed the creation of Nintendo-inspired worlds initially, it blocked attempts to generate a Kingdom Hearts-style environment, even when specific character names were removed and replaced with descriptions. In one case, Genie generated a thumbnail featuring characters that looked nearly identical to Disney and Square Enix properties, only to block the full experience from rendering.

Rivas explained that Project Genie is designed to follow user prompts and that Google is closely monitoring feedback. He added that Genie 3 was trained primarily on publicly available data from the web, which may explain why certain character behaviors—like gliding in a Zelda-like world—emerge organically from patterns the model has learned. Shortly before publication, Google began blocking Mario-themed generations altogether, citing the “interests of third-party content providers.”

Even setting IP concerns aside, Project Genie struggles as an interactive medium. The strict 60-second limit, unreliable controls, lack of audio, and frequent visual inconsistencies make it difficult to stay immersed. Compared with handcrafted video games—or even simpler indie experiences—the gap in quality is substantial.

Project Genie is undeniably more advanced than similar AI world-generation tools available just a year ago. But it still feels like a prototype searching for its purpose rather than a technology on the verge of mainstream adoption. Fruchter has spoken about a future where the lines between games, film, and interactive media blur, but for now, that vision remains distant.

Perhaps expectations should be adjusted. Project Genie is, by Google’s own description, an experiment. And like many early AI demonstrations, it’s better at sparking curiosity than delivering lasting engagement. For now, at least, AI-generated worlds are more interesting to peek into than to stay inside—and the genie, it seems, is still firmly in the bottle.